Hello! It’s been a while – a very long while, we didn’t mean for almost 6 months to lapse – and there’s been a lot going on since we last checked in here. We’ll do our best to start catching up on the past five months (a very exciting and busy five months!) since our book The German-Jewish Cookbook was published in September. First, it was such an exciting experience to hold an actual book in our hands – OUR book – after working on it for so long. We realized the project took the better part of nine years (!!!) as we can date the early stages of our research back to 2009. Phew.

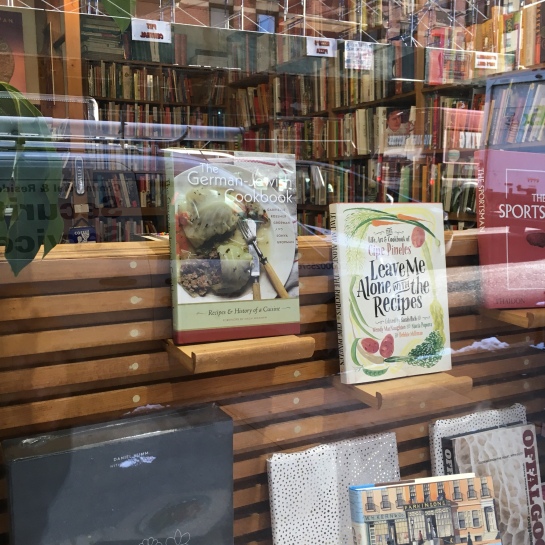

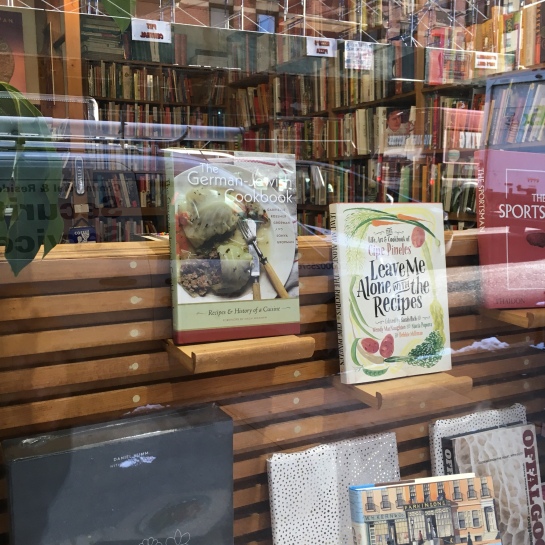

It never gets old seeing our book “in the wild”, and it was especially great to see it in the window of Kitchen Arts & Letters, the wonderful culinary bookstore in Manhattan – not only because it’s a shop we’ve adored and have been visiting and shopping at forever, but also because Nach Waxman, the founder, wrote the foreword to our book. And Matt Sartwell, the co-owner, is so helpful in so many ways and is an all-around mensch. We were especially tickled to see the book sitting next to Leave Me Alone with the Recipes by Cipe Paneles in the front window (look it up if you’re not familiar with this special book!).

The German-Jewish Cookbook in the window of Kitchen Arts & Letters, the culinary bookstore in NYC.

In many ways the world has become a tad bit smaller for us since the book was published as we began connecting with interested readers in real life, meeting people at book events and/or hearing their feedback about the book in comments and emails. Making these connections feels so important, as it is truly the main reason we wrote this book – as a way to preserve and share the food of a culture, something that unifies people.

We would love to hear your feedback and see photos of the recipes you are making from the book! Please share photos on social media if you can, using #GermanJewishCookbook so we’ll find it — either on Instagram (use #GermanJewishCookbook and tag @sonyagrop) or on Facebook (Facebook.com/German Jewish Cuisine), or Twitter (@Ger_Jew_Cuisine). Or simply email us photos: german.jewish.cuisine@gmail.com

Butter cookies (heading into the oven to bake) that we brought to our book talk at Porter Square Books in Cambridge, MA last November.

We have had many opportunities to meet people at the numerous book events we have had thus far on both the east and west coasts — in New York City, Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles to date — where we have held events at a wide array of venues: book stores (both general and those that specialize in culinary books), universities, community centers, synagogues, Jewish organizations, and the NY Public library. Our events have been varied in nature, including book talks and readings (many of which include food tastings), cooking demonstrations, cooking classes, and restaurant dinners with special menus featuring our recipes. We are looking forward to meeting many more readers at future events. We have upcoming events scheduled in New York City; Boston; St. Petersburg, Florida; Germany (Berlin, Bamberg, and Munich); Ann Arbor, MI, with more to come. In the near future, we are excited about these upcoming events:

- February 28th – a book talk at Espresso 77 in Jackson Heights, NYC

- March 1st – a discussion about the book with the inimitable Mimi Sheraton at the 92nd St. Y in NYC

- March 20th – a panel discussion with us and Atina Grossman and Jeffrey Yoskowitz at the Leo Baeck Institute (at the Center for Jewish History) in NYC

- March 27th – a talk we will present at the Culinary Historians of Boston (in Cambridge, MA)

Please visit our events page for a complete listing of upcoming events. Please note: we will update the events page as additional events are added, so please check back.

Gaby speaking to the audience during our Jacques Pépin lecture at the Gastronomy Department at Boston University in November.

It is always exciting for us to meet people who are of German-Jewish ancestry who want to connect with their roots and share their family stories and/or their own food memories. We have met such people at just about all of our events across the country. One person brought along a bottle of fruit syrup that was empty but had a perfectly preserved (and beautiful) label still gracing the front. The bottle represents a strong link to her culinary past, as well as to her parents and her childhood, and she told us she keeps it carefully wrapped in a safe spot. Another person took a bite of Berches (the German version of challah) that we served at one of our events and tears started falling from her eyes – she told us this was the first time she was tasting this bread in 40 years, and that it tasted just as she remembered it!

This long-empty bottle of German strawberry syrup was brought by someone of German-Jewish background to one of our events.

It is also exciting to meet people of German background (non-Jews) who often recognize their own past in our recipes, foods that were perhaps made by their parents or grandparents. After all, German-Jewish cooking – which is both German and Jewish – is a culinary tradition which came to a halt in Germany in the 1930s during the Nazi era, when Jews fled. This resulted in a food tradition that in many ways is frozen in time, rendering it “old-fashioned”. The food we present was eaten before that time, and also continued to be eaten in varying degrees of adaptation by emigres in their new homes, in foreign countries.

The special German-Jewish menu listed on the chalkboard at Gravy restaurant in Vashon, WA last October.

It is also exciting to meet people who are not Jewish, nor German, who comprise a good part of our audiences who are interested in our book and its food traditions simply because they want to discover a new style of cooking. Some seem fascinated with the fact that the recipes are embedded in a story that recounts memories of past generations. Others, in the details of this central European cuisine which highlights ingredients that are fresh and seasonal – and includes more vegetables than either German or Jewish food is generally given credit for.

We were thrilled to see how Chef Dre Neeley of Gravy, a restaurant on Vashon Island, near Seattle, interpreted our recipes for a special dinner menu he and partner Pepa Brower served last October. It was a 7-course meal, which heavily featured the incredible selection of fish available in the Pacific Northwest. Note that the menu is listed on the chalkboard in the photo above (though the amuse bouche of chopped liver pâté, shown below left, was not listed). On the right is salmon in aspic.

Chicken Liver Pate by chef Dre Neeley, served with bread by Ben Campbell at Gravy.

Salmon in Aspic served at Gravy.

The fact that we are a mother-daughter team ALSO fascinates many, and we think one of the main reasons is that it emphasizes the multi-generational aspect of our project. But it also undoubtedly makes everyone wonder whether they’d be able to survive a nine-year project with their mother or daughter with humor and good nature intact. We have –though we’ve certainly traversed our fair share of stormy weather.

Sonya (left) and Gaby (right).

A few more photos of events and people we’ve met during the past five months of book events. It was a delightful afternoon and such an honor to do a book talk at Omnivore Books in San Francisco. Many friends and family showed up on a sunny day.

Sonya (left) and Gaby (right) with Celia Sack (middle), owner of the wonderful shop Omnivore Books in San Francisco.

In Seattle, we taught a sold-out cooking class at Stroum JCC. We created an ambitious menu, cooking and baking an entire meal. There were plenty of tasks for everyone (peeling, grating, rolling, chopping, beating, boiling, draining, icing, etc) and when everything was done we sat together at a long table and schmoozed as we ate. Lisa Hurwitz (front +center in photo below, right) organized the class.

A cooking class at the Stroum JCC in Seattle made an entire meal. People in the front are grating potatoes for dumplings, while those in the back are preparing mushrooms, cabbage slaw, and making chocolate hazelnut cookies.

We then feasted on all the dishes we prepared!

Book Larder is a delightful bookshop in Seattle that specializes in culinary books. It also has an in-store kitchen where cooking demos and classes are hosted. The in-house chef, Amanda, baked one of our cakes to serve during our evening book talk!

The audience at Book Larder in Seattle during our book talk.

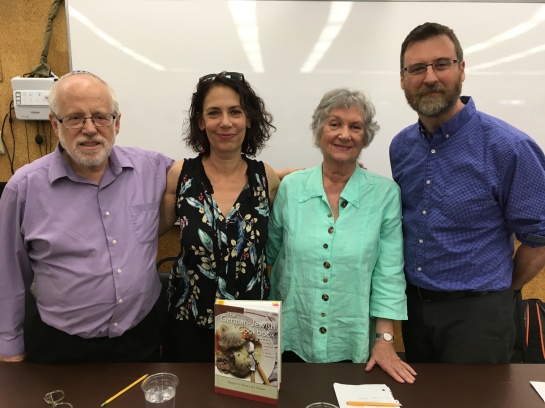

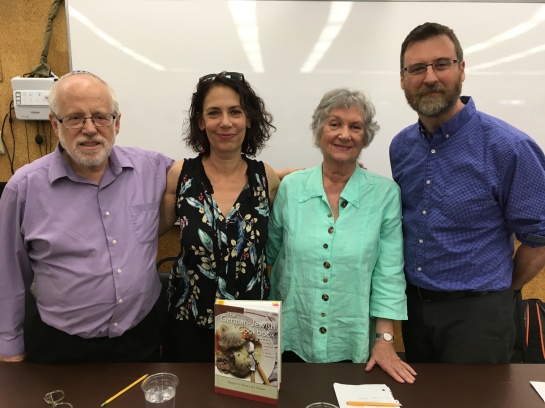

And finally, we were so honored to be joined by Steven Lowenstein – historian and author of numerous books on German-Jewish culture – at our book talk at University of Southern California in collaboration with Hebrew Union College. Professors Paul Lerner and Leah Hochman invited us to do this talk, which had a great turnout of both students and members of the public.

(left to right) historian Steven Lowenstein, Sonya, Gaby, Professor Paul Lerner, University of Southern California

— Sonya & Gaby